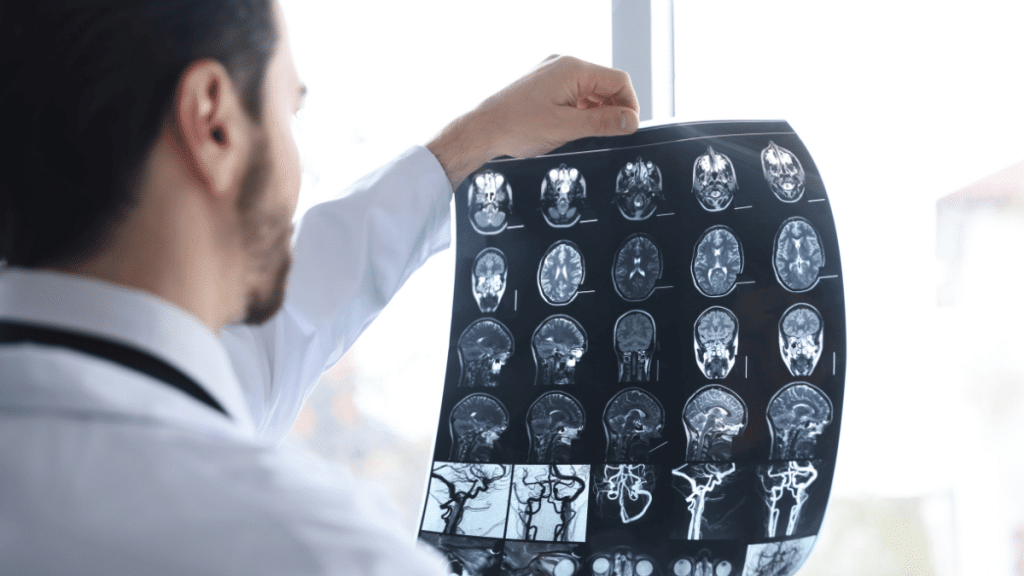

The progression of a traumatic brain injury (TBI) is not simply an event. It is a disease process that begins the moment the head is subjected to a harmful force; it then evolves and continues for days, weeks, months, or even years. There are approximately three million emergency department visits, hospital admissions, and deaths per year in the United States alone due to a TBI that occurs about every nine seconds. Worldwide, this figure is estimated to be around 70 million annual TBI events. Thus, understanding how TBIs occur and how medical providers respond to them today is essential to both the patient/family unit and the medical community.An individual sustaining a traumatic brain injury (TBI) is defined as any external physical force causing a disruption in normal brain function or structural damage to the brain. The type of force may be either a direct blow to the head; rapid acceleration/deceleration (e.g., automobile accident); an object penetrating the skull; or a pressure wave generated from an explosion. Most TBIs are classified as “closed-head” injuries, which means there was no fracture or break of the skull. However, the brain can still come into contact with the inner surface of the skull, potentially damaging delicate structures within it, such as nerve fibers and blood vessels. Penetrating and blast TBIs are complex and add a layer of difficulty to treatment; however, they both share the same basic problem: the brain does not adapt well to rapid movement within a confined space.There are several methods that clinicians utilize to classify the severity of a TBI. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a 15-point scale that evaluates eye opening, verbal responses, and motor responses to assess the patient’s degree of consciousness. Mild TBIs (scores of 13 – 15 on the GCS) include concussions. Moderate TBIs (scores of 9 – 12 on the GCS) indicate injury that requires immediate attention. Severe TBIs (scores of 8 or less on the GCS) are life-threatening. While mild TBIs make up the majority of TBIs, the designation “mild” may be misleading. Approximately fifty percent of patients diagnosed with mild TBIs will continue to experience symptoms six to eight months post-injury, and a small percentage will not recover to pre-morbid baseline.Children under the age of five are vulnerable to TBI because they fall before developing sufficient protective reflexes. Teenagers and young adults are likely to suffer from TBIs from participation in contact sports, operating a vehicle, and engaging in other high-risk behaviors. Adults sixty years old or older are most susceptible to falls in the home and, as such, are at the highest risk for suffering a TBI. Falls now account for more than 50% of all TBIs in the United States, with motor vehicle accidents and strikes against an object ranking second and third, respectively. Military personnel have been experiencing increasing rates of blast injuries over the last two decades.TBIs progress through two distinct phases. The first phase of injury occurs at the time of the incident and cannot be reversed. The secondary phase of injury occurs subsequent to the primary phase and results from swelling, inflammation, hypoxia (low oxygen levels), hypotension (low blood pressure), seizures, and various biochemical cascades causing further injury. Research conducted by trauma professionals, including Dr. Martin Schreiber of Portland, has shown that preventing the secondary phase of injury through the use of early physiological stabilization is one of the most effective methods of improving survival rates and reducing long-term neurological deficits.Assessment for a TBI typically begins in the field. First responders assess the patient’s level of consciousness, pupillary reactions, and signs of spinal cord injury. Prompt bleeding control is also crucial. Trauma surgeons, like Dr. Alexander Eastman, who is a leader in the Stop the Bleed initiative, stress that quickly stopping bleeding before taking a patient to the hospital can prevent serious problems that worsen brain injuries.Upon arrival at the emergency department, a non-contrast head CT is utilized as the primary radiographic modality to identify acute hemorrhaging and/or cerebral edema requiring immediate intervention. As of 2025, the use of blood-based biomarkers, specifically GFAP and UCH-L1, has become commonplace in many hospitals to assist in diagnosing TBI. These FDA-approved proteins can aid in the determination of whether a CT scan is necessary in selected mild cases of TBI. If CT scan results are negative but the patient continues to exhibit symptoms, an MRI using advanced techniques such as diffusion tensor imaging can detect microscopically damaged axons.Management of moderate to severe TBI in the hospital is based upon several strict priorities. Blood pressure must be maintained to provide adequate cerebral perfusion. Oxygen levels must be kept near normal. Careful regulation of carbon dioxide levels is required. Monitoring of intracranial pressure is common in comatose patients. Osmotherapy agents such as hypertonic saline and mannitol are commonly employed to reduce cerebral edema. In the most severe cases, surgical decompression craniectomy may be performed to allow for cerebral swelling without compression of the brain tissue.While medications have a limited role in the treatment of TBI, they do have a specific application. When administered early, tranexamic acid has been found to decrease mortality due to hemorrhaging; however, it has not been found to significantly enhance long-term neurologic recovery. Mild hypothermia (targeted temperature management) is currently the recommended method of treatment for mild to moderate hypothermia rather than extreme cooling, which has been shown to cause harm in numerous large-scale clinical trials.Rehabilitation and recovery of function after TBI represent one of the most promising areas of advancement recently. Amantadine is FDA-approved to enhance cognitive recovery in individuals with moderate to severe TBI. Various international neuropeptide treatments continue to demonstrate some functional improvement. Multiple late-stage stem cell trials (including SB623) have shown significant motor improvements in selected patients at one year post-stem cell transplantation. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation is becoming more commonly used to treat persistent depression, cognitive impairments, and chronic pain in patients with TBI. Many Veterans Administration facilities now provide hyperbaric oxygen therapy, previously controversial, to patients with chronic post-concussive symptoms.Significant long-term sequelae exist for survivors of TBI. Many of those who sustain a concussion will continue to experience post-concussive syndrome, chronic headaches, dizziness, mood disturbances, and cognitive fogginess for extended periods of time. Each successive TBI increases the risk of developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Survivors of TBI have increased risks of developing post-traumatic epilepsy, hormone deficiencies, depression, and suicidal ideation.Preventative measures are the most effective intervention available to reduce the incidence of TBI. Use of helmets reduces the risk of severe head injury by up to 85%. Wearing seat belts and having airbags installed in vehicles dramatically reduces the risk of fatal crashes. Home modification and balance training can significantly reduce the rate of fall-related injuries among elderly individuals.

Cristina Macias is a 25-year-old writer who enjoys reading, writing, Rubix cube, and listening to the radio. She is inspiring and smart, but can also be a bit lazy.